Constructing visual reality

Chapter 3 ("3-D Graphics and the Construction of Visual Reality") of Reality Media describes how AR and VR depend on principles of computer graphics (CG) to construct their version of visual reality. In 3D CG, computer hardware and software must explicitly create all the elements of the scene that analog and even digital photography get "for free" when they focus and record the light from the world. The form and shape of the objects, the lighting and shading of the scene, and (for moving objects) the physical behavior must all be calculated and recalculated each time the user moves their head and changes perspective. Photorealism, the holy grail of computer graphics for decades, is often understood as making a CG scene that is indistinguishable from reality. But, as the name suggests, it measures reality in terms of photography (and film). The ideal photorealistic image would be indistinguishable from a photograph. A photorealistic animation wants to be a live action film. A perfect photorealistic graphic would achieve for the digital medium what the LaCiotat myth promised for film.

We argue in Reality Media that in film the LaCiotat myth is never realized. The viewer always knows at some intuitive level that she is watching an technical illusion. What she experiences is the double character of the LaCiotat effect. In the case of CG, when photorealism falls short, the image or animation leads to a feeling of the uncanny. The term uncanny valley is used to describe CG images, particularly of humans, that come close to perfect photorealism, but do not achieve it. They seem eerie. And everyone assumes that it is better to be a cartoon character than an eerie, almost-human image in 2D or 3D.

We argue in the book, however, that the uncanny is not bug, but rather a feature of all reality media. A sense of the uncanny is another name for the la Ciotat effect. The uncanny can provoke a feeling of wonder as well as uneasiness. The audience of the Lumière brothers' film had the same feeling as they watched the approach of a train that they knew could not be real.

In the first room of the immersive gallery, we illustrate principles of computer graphics. You will also find videos explaining the uncanny valley, but failing to account for the la Ciotat effect.

Spatial tracking and Sensing

Chapter 4 of Reality Media describes how the computer tracks both itself and the user's place in the world (AR) and the imagined worlds of VR. In the second room of this immersive gallery, we demonstrate what tracking in six DOF means. We also illustrate the uncanny quality of the 3D reproduction of the world enabled by LIDAR and digital techniques on the latest smart phones.

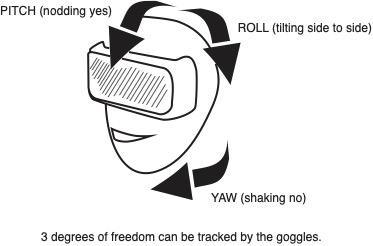

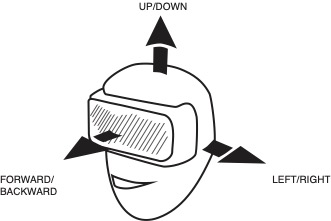

Tracking the user is essential in order to position graphics and other data in her environment. In our three-dimensional world, a user can orient her head through three kinds of movements (up and down, side to side, and tilting right and left), and she can move her body in three ways (up and down, right to left, and forward and back). A user has six so-called degrees of freedom (DOF). Some VR and AR applications can make do with just knowing the orientation of the user (where she is looking). But if the user can move around while using the application, then the system must track all six DOF.

Tracking the user's hand movements or eye movements can permit her to interact with digital materials: text and especially 2-D and 3-D graphic objects can become dynamic and responsive. The user can press virtual buttons to start a video or animation or pick up virtual objects. This responsiveness can contribute to an uncanny quality in the spaces of AR and VR, although in different ways. Responsiveness together with photorealism can contribute to the sense that a VR experience is more than simply watching a 360° video, but rather that the user is inhabiting a virtual world. We discuss presence in a chapter of Reality Media and illustrate it in the gallery Presence and Aura.

For AR, sensing technologies are becoming increasingly sophisticated and enabling the applications not only to determine where the user is in the world; they are also beginning to construct 3D maps for the world around the user, buildings and potentially rooms and their contents. They may also send this information back up to servers controlled by companies who made the application. With such applications potentially running on millions of phones, the environment, especially the urban environments with so many phones, becomes uncannily alive. We explore the social and cultural implications in a chapter on privacy and public space in Reality Media and in the gallery Privacy and Public Space. We explore the vision/fantasy of an ultimate 3D mirror world or metaverse in the Future Gallery

Enter the Graphics and Sensing Gallery .